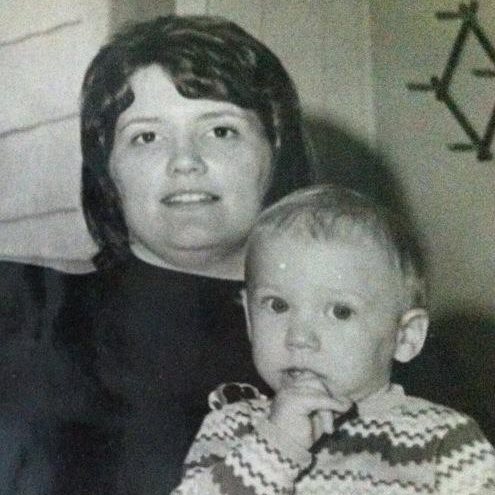

I remember her smile and how her face would light up. Her smile, that rarely left her face. Her smile that made people feel welcome and cared for. And…her laugh. I was a hyper, silly child, but she always laughed at my corny jokes and senseless humor. I remember that I could always make her laugh – I remember her laugh.

I don’t remember what we talked about that day…but I do remember hugging her before I left. She had always struggled with her weight and had lost a lot of weight that year. She had tried every diet you can imagine through the years and nothing had worked, but finally she was able to shed all that extra weight and she was proud of herself for it. When I hugged her, it felt like half of her, I could feel her bones, and to my shock, my hand rested on a huge knot the size of a softball on the right side of her back.

I lost the embrace and stepped back, holding her shoulders and looking into her eyes. I said, “Mom, what is that on your back?” She told me that she had been to the doctor about it and that he said it was just a benign cyst and nothing to worry about. I paused before I spoke again. My look very serious now. I said, “I don’t agree, Mom. Did you get a second opinion? If I were you, I would see someone else about this.”

My mom then proceeded to show me these same “benign cysts” in various places all over her body. With each one, fear grew inside of me and I know she must have become afraid as well because her look changed. In that moment, we both knew it. “This is serious, Mom,” I said. “I will get another opinion,” she said. And, she did. And, yes, it was cancer.

“Andy.”

Her voice broke the silence of the piercingly dark hospital room.

“Are you awake?”

“I am,” I replied.

“I want to tell you something,” She said. “Come sit with me.”

I got out of the hospital recliner where I had slept for several nights keeping vigil over her as her decline through six months of chemo and radiation had stripped her of the strength to even stand. I sat down on the bed next to her and held her hand.

“When I was in seminary in New Orleans, I had a friend who was gay. We spent a lot of time together and enjoyed a wonderful friendship.”

“Oh,” I said, “I didn’t know that.”

She continued, “Yes, he was my best friend at seminary. We had several classes together as well. One day I arrived at class before he did and took my usual seat. Another seminary student who I was not familiar with at the time arrived and sat in the seat directly in front of me. When my friend arrived, he sat in the seat in front of this other student. He turned, leaned out, and started talking to me around this other student. We said a few things back and forth.”

She paused after saying this and took a few deep breathes. And her usual soft caring voice changed. It sounded angry as she continued to tell me the story, “All of sudden, the student sitting in front of me leaned out to block us from being able to see each other and he started yelling at my friend, ‘You turn around, queer, and stop talking to her! Don’t you talk to her!’ My friend didn’t speak a word and embarrassingly turned around to face forward in his seat.”

My mom started to cry, and she squeezed my hand tighter.

I gave her a moment and then asked, “What did you do?”

She continued to cry and when she was able to gather herself, she said, “I didn’t do anything. I didn’t say anything. I just sat there and watched this hateful person be mean to my friend and I didn’t do anything.”

I could hear the shame in her voice. Her regret that she could not go back and do it differently. We sat there in the darkness holding hands, my mom finally settling herself.

And then she said, “I don’t know how people can be so hateful, but I want you to know that I think you and Dana have it right.”

She was referring to our belief that we are all God’s children and beautiful in our own way just the way we are.

She said, “I should have said something. That’s what I wanted to tell you. That’s all I have to say.”

I went back to my chair. And we both sat there in the silent darkness.

“I love you,” I said breaking the silence again. “Thank you for sharing that with me.”

“I love you too,” she replied.

And that was it. Those were the last words she ever spoke to me. That was the last time I heard that sweet, calm, caring voice. She was put on a respirator and induced into a coma early the next morning. She died two days later.

As Mother’s Day approaches, my heart aches when I think back on the last time that I heard her voice. But I am also grateful that I was able to be there to hear her confession…to hear her last story…and to, again, as so many times throughout my life, be affirmed and blessed by her wisdom and care.

I love you, mom. I miss you every day.

-Andy McNiel, May 11, 2019